Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) (pronounced “ICK-see”) is a procedure used in conjunction with IVF in which a laboratory technician, using a microscope, attempts to inject a single sperm directly into each egg. ICSI is often used if the male partner has very low sperm count, low sperm motility, or poor quality sperm. If fertilization occurs after ICSI, the embryo may then be transferred into the uterus.

The use of ICSI and these sperm extraction techniques has greatly improved the ability of Reproductive Endocrinologists to treat male factor infertility. However, these treatments are not effective for men who do not produce any sperm at all. In these cases, donor sperm would be necessary.

How is ICSI performed?

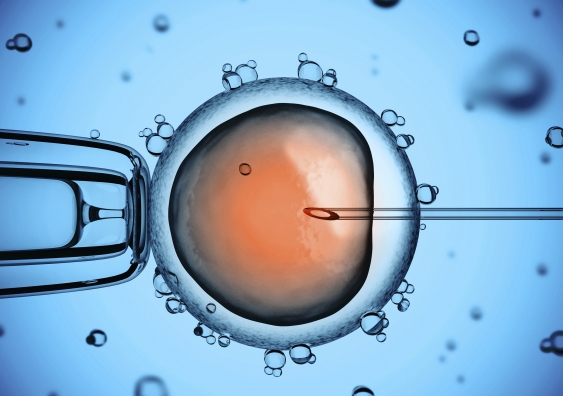

The mature egg is held with a specialized holding pipette. A very delicate, sharp and hollow needle is used to immobilize and pick up a single sperm.This needle is then carefully inserted through the zona (shell of egg) and in to the cytoplasm of the egg. The sperm is injected in to the cytoplasm and the needle carefully removed. The eggs are checked the next morning for evidence of normal fertilization.

Who is ICSI suitable for?

When a sperm count is considered too low, or the sperm have low or slow motility or a very high proportion of abnormal shapes, or when there high levels of antisperm antibodies, fertilisation rates with conventional IVF are often reduced or there may be no fertilisation at all. The reasons for this are not always clear, although it is known that the sperm fertilizing function can be affected by all these factors. Rather than risk the terrible disappointment of no fertilization after egg collection, if a semen analysis shows one or more ‘male’ factors then we would recommend ICSI as the treatment most likely to give a successful outcome. ICSI is used to overcome these problems by carefully injecting each ripe egg with a single sperm picked up in a very fine glass needle.

Occasionally, IVF using sperm considered normal may result in unexpected lack of fertilization. In these rare cases we would recommend another attempt using ICSI, even though there does not appear to be any obvious male factor present. This way, if there is a problem with the sperm and egg attaching together before the sperm enters the egg, we are able to try to overcome it by placing a sperm directly inside each ripe egg.

Where testicular sperm is used in cases of failed vasectomy reversal, obstructive azoospermia, or other causes, ICSI is necessary. Sperm retrieved surgically (by PESA or TESE) is usually immature and present in insufficient quantities for standard IVF.

What happens during ICSI treatment?

From the patient viewpoint, ICSI is very much the same as IVF. It is what happens in the laboratory that differs.

Eggs are retrieved as described on the IVF page, a semen sample is produced by the male partner (in most cases), and then both eggs and sperm are specially prepared for ICSI. Some hours after egg collection, each egg which is mature (generally at least 80% of those collected) is injected with a single sperm under a very high-powered microscope. We try to use sperm which are seen to be motile and normal in shape. After the ICSI procedure the injected eggs are placed in an incubator and inspected the next morning to see how many have fertilized.

This is typically around 60% of those injected, similar to conventional IVF, although it varies from case to case. More than 90% of couples having ICSI can expect at least some of their eggs to be fertilized. Following the fertilisation check the early ICSI embryos are grown in the lab and used in exactly the same manner as those from IVF.

For some men with no sperm in the ejaculate it is necessary to perform a surgical sperm retrieval before the day of egg collection; the Surgical sperm retrieval web page has more information.

As ICSI is a delicate technique requiring specialist equipment and expertise, it costs more than straightforward IVF.

Are there any risks with ICSI?

• the injection technique may sometimes permanently damage individual eggs. The overall damage rate is low (below 10%) but can be higher for some patients depending on egg quality at the time.

• very occasionally there may be a complete and unexpected lack of normal fertilization of any of the eggs collected and injected, even with ICSI. When this happens with a good number of eggs in an ICSI cycle, or if it occurs in more than one ICSI treatment, it would appear to be a more complex problem than first thought, and we may consider recommending the use of either donated sperm or eggs for further treatment in some cases, depending on individual circumstances. Please see ‘Donor Treatment’ for more information about using donated gametes. |

• It has been reported that the risk of miscarriage seems to increase in proportion to the severity of male subfertility, especially where surgical sperm retrieval is necessary.• ICSI is still a fairly new technique – it has only been in routine use since the early 1990s. There have been some concerns regarding the safety of the technique – does injecting a sperm right inside an egg cause long term damage to the egg? Can selecting a sperm for injection bypass some of the natural selection processes which normally make it unlikely that an abnormal sperm would result in pregnancy? If sperm from a sub-fertile man is used to achieve a pregnancy which results in the birth of a son, will the child inherit his father’s fertility problems?

• There have been numerous studies carried out to try to find answers to these questions. Some have shown that babies born after ICSI show new chromosomal abnormalities in up to 3% of cases. Others have suggested that there may be a slight increase in the number of minor birth defects in ICSI babies compared to the general population, although these may be more associated with premature births and multiple pregnancies than the ICSI procedure itself. Several studies have compared the development of ICSI babies with that of children conceived naturally and from IVF, and although there were some early suggestions that ICSI children develop slightly more slowly than their non-ICSI counterparts, other more recent studies have not borne this out.

• Different studies have shown a higher rate of ‘sex chromosome’ abnormalities – possibly due to the fact that the sperm used for ICSI carried these abnormalities and may have been the reason why the couple could not conceive in the first place. It is now known that some men have Y chromosome deletions which affect their sperm function and hence fertility, which may be passed on to any sons conceived with ICSI using this sperm. Some men who have no sperm in the ejaculate may be carriers of genes linked to Cystic Fibrosis.

• In the light of these findings we recommend strongly that couples undergo genetic testing before starting treatment if the man has severe oligospermia (low count) or azoospermia (no sperm in ejaculate unless due to vasectomy). This involves a blood test and genetic counselling if needed.

• If you have any concerns regarding these important issues please raise them with us – but also bear in mind that ICSI is relatively new and we may not be able to provide definitive answers for some years to come.

Is the baby at any risk?

All parents face the risk that there may be something wrong with their child at birth – a congenital abnormality. The risk is around 2 to 2.5%. A number of research papers have suggested that the risk of having a congenital abnormality following ICSI is the same as occurs in in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and in the general population at large who are not infertile